- Home

- C. C. MacDonald

Happy Ever After Page 10

Happy Ever After Read online

Page 10

It’s possible that physical changes that occur in an expectant mother’s brain could explain the phenomenon. During pregnancy, a mother’s brain rewires to improve her sensitivity to emotion and her ability to read facial expressions. These adjustments make mums more attuned to their babies’ needs once they’re born. However, in order for these new superpowers to develop, certain other areas of the brain, the areas that control everyday abilities like judgement or short-term memory, are temporarily hampered.

NINE

6 weeks

A small pigeon stands on the front step of Naomi’s house staring at her as Prue struggles in her arms. Naomi feels seasick. The pregnancy nausea has been relentless this time, ten times worse than with Prue.

The bird has made two attempts to fly away but there’s something wrong with it. Its head bobs as if it might fall off its neck at any moment. Naomi hates birds. In corporate seminars and team-building exercises in her past life, whenever she had to reveal a ‘fun fact’ about herself, she would always tell everyone about a poem she wrote when she was a teenager about the pigeons on the seafront in Bournemouth and how much she hated them. It talked about their eyes being the colour of fire but without warmth. ‘Cold, soulless and dripping with desperation.’ The poem wasn’t very good. She’d found the original in a school textbook a year ago and posted it on Instagram, it got a lot of likes.

In addition to Prue, Naomi’s carrying her little girl’s nursery rucksack and a full canvas shopping bag. They’re half an hour late for Prue’s afternoon nap because Naomi thought her baby bag had been stolen at Ladybird’s Landing. It hadn’t; Lara found it on the changing tables in the ladies’ toilets. She wants to scream out for Charlie but he’s at the top of the house and wouldn’t hear her. This is his fault. He’s been shooting them during the day when she’s not there, this is probably one that he only managed to maim. Prue’s gone quiet. She loves animals but she can sense this one’s wounded and has the potential for malignancy. She squirms higher on to her mum’s shoulder and a wellington-booted foot kicks into Naomi’s ribs making her grunt in pain and drop the shopping bag on to the front path.

Naomi is exhausted. The biennial’s six months away so she’s having to work in the evenings after Prue’s bedtime and, due to the builders layering endless barrels of cement on to the walls in the basement, she’s wiping away cement dust from the whole of the ground floor three or four times a day.

Tiredness has slowed her, as if her mind and muscles are steeped in molasses. When she’s looking after Prue she can’t find the energy to engage with her properly, the best she can manage is sitting in a circle with her cuddly toys and being the least enthusiastic guest at her tea party. In the evenings she can’t face talking about logistics with Charlie so the builders are doing things they haven’t been asked to, cutting corners most likely. In the last few weeks the fridge somehow never has more than some browning green beans, a bag of radishes and a jar of mango chutney that she’s been giving far more attention than she should. It’s just spicy jam, she’s been telling herself as she spoons it on to partially thawed crumpets.

She’s been thinking about Sean. Waking up between four and five every day and as the mist of sleep clears he is the first figure that slinks into her head. She gets the chemical kick she got every time she used to see him at The Bank of Friendship and then there is no hope for her sleeping. So she spends the next hour and a half, before Charlie’s alarm bleats into life at six thirty, trying not to think about the man she had sex with in a swimming-pool changing room. Sean’s absence has intensified her memory of him and distilled their moments together into absolute clarity. Yet her recollections of him feel distinct from other parts of her past, like they didn’t really happen to her, scenes from a film she saw many years ago that have stayed with her. She has managed to both forget him and put him on a pedestal. The mind’s capacity to lie to itself is extraordinary. She and Charlie visited Auschwitz together as part of a city break to Krakow. They barely talked while they walked round the museum and the gas chambers, but in their hire car on the way back to their hotel, they laughed and joked and sang along to a David Guetta song on the radio. Being there amongst that horror didn’t feel real, like they had woken up from a horrible nightmare. Their subconscious did that little clean-up job without their permission and it’s clear that it can do the same thing for our own behaviour, however appalling.

In those endless black-night mornings, she replays her and Sean’s friendship. The thought of sex turns her stomach at the moment, so it’s less an erotic reverie and more a long-form exercise in esprit de l’escalier. She forensically picks apart the times when she should have said something different, behaved better. She doesn’t always castigate herself for encouraging his attraction to her. There are moments when she thinks that her biggest error was telling him she’d made a mistake. Naomi shouldn’t be thinking like this. She’s been given a get-out-of-jail-free card and she’s not going to do anything stupid, but perhaps if she’d left him a sliver of doubt, a thin basement window of opportunity for The Lumberjack to climb in through … In her marital bed she’s safe to luxuriate in thoughts like these and, some of the time, she doesn’t even feel guilty for it because the whole episode is exactly that, an episode, finished.

The wind picks up some rain and Prue scrunches her face, lower lip trembling, readying to cry. Naomi looks up at the top-floor window and sees the glow of Charlie’s lamp but there’s no sign of him rescuing her from the pigeon. Every time it flaps its wings it gets inches off the ground and, on returning to earth, its body stutters frantically. Naomi edges towards it with no idea of what her plan is. A few steps away and there’s another frenetic flap, the spiny rattling of feathers on their newly painted door. Naomi puts Prue down behind her, hands her her backpack to hold and picks up the shopping bag. The icy rain turns to sleet. Naomi strides forward, subconsciously swinging the bag whose bottom layer is built from cans of chickpeas, chopped tomatoes and tuna. The bird can sense the movement and begins to hop up, flapping its useless wings, straining to get off the steps. Naomi puts one foot on the bottom step and swings the bag at the bird gently, intending to steer it around her and back out into the open. She guides it past her legs and out of the porch and then it stops, exhausted by the effort, right in front of Prue. Naomi opens the front door, intending to grab Prue, lift her over the bird and into the house. Then the bird starts flapping hard and rises up towards the level of Prue’s face, the little girl banshee-howls and throws her rucksack on the floor. Naomi piles her shopping bag into the side of the bird, the full force of eight tin cans smashing it into the wall of their front garden. Prue screams and runs towards the road where she’s stopped by the metal gate that Naomi had Charlie install.

Charlie’s there in the doorframe now. He strides out in socks, leaving footprints on the wet paving stones, and goes to get Prue from the gate. Her screams abate as he holds her into his chest. As he passes Naomi his expression asks her, What the hell’s going on? She purses her lips tight together and gives him a murderous look.

The pigeon looks dead.

TEN

‘Congratulations.’

‘Thanks.’

‘You must be delighted.’

‘Yeah, we are.’

‘You said to me that you thought it might never happen.’

‘It’s great.’

‘Naomi’s doing OK?’

‘She’s knackered and feels sick. Apart from that … She’s … not had the energy for anything and so I’ve had to pick up the slack and – I know I need to just man up and— ’

‘That’s not a helpful phrase.’

‘It’s been hard. Doing everything, round the house, with Prue. Anyway, it’s fine. It’s great.’

‘Great.’

‘She’s really jumpy. It was different with Prue. She was like a warrior. We went walking in the Mendip Hills when she was seven months’ pregnant. This time, it’s early days and she’s already super sensitive to eve

rything. Last night she woke me up at three because she thought she heard something in the front garden. Said she heard a bin lid or something. I had to go down and check and, course, there was nothing there. Where we live, when wind picks up off the sea it really whistles around the house. There’s always a lot of noise, floorboards creaking, that sort of thing, and she’s constantly up in the night because of it.’

‘Not sleeping well is very common in pregnancy.’

‘That’s what she says about everything. After shouting at me for eating a packet of crisps next to her the other night, she didn’t apologise, she just told me it’s very common to find things like that infuriating.’

‘Last time you said you were finding it easier to recognise the negative thoughts as they occurred and you were feeling good about some new friends that you’d made.’

‘They’re just people I play football with.’

‘You called them friends last time, what were their names? The ones we talked about.’

‘Er, Tayo and Salinger, Sali.’

‘It really seemed that spending time with them was helping you tap into your own positivity again.’

‘I haven’t seen any of the boys from football for a bit.’

‘Why not?’

‘There hasn’t been time.’

‘It’s so important to make time for things outside work, outside your family.’

‘That’d go down like a glass of warm gin.’

‘You don’t want to head back into that state of resentment. The scores on your measure are down.’

‘Not surprising.’

‘Why is it not surprising?’

‘Naomi and I used to love getting drunk together and not going out. We’d arrange to meet friends and work our way through a bottle of rum and we’d keep texting them, telling them we were on our way and we’d never turn up. We found it so funny because we knew that our little gang of two was the best. We’d talk about philosophy and religion, she’s got school friends who are super-Christian so she’s fairly tolerant of people’s beliefs where I think religion’s a load of rubbish so we’d stay up all night, me trying to convince her that God definitely doesn’t exist and— That sort of stuff, anyway. It was our little world and it was perfect. And, you and I have talked about this, Prue’s now there and we’ve got a different little world and it’s not perfect yet but I can see how it will be one day but this …’

‘You’re not excited?’

‘I’m excited that we’re going to have the family that Naomi wants and I always wanted kids but I also want to talk about, I don’t know, what’s going on in the Middle East or the future of infrastructure in urban centres. I want to talk about those things, with Naomi, like we used to, because she’s much cleverer than me and it made me think. I don’t think now because it’s always the same conversations. When did Prue sleep? What did she eat? Is she ill? Did you buy that thing she needs? It’s necessary, I get that, but it’s boring. I wash and I cook and I try to work and I feel like an automaton, a robot. But a broken one. The next baby is going to come and it’ll get ten times harder because everyone says it gets ten times harder and I’m going to be back here with you, talking all this self-indulgent bloody … Sorry.’

Charlie’s eyes fill and Amy hands him the man-sized box of tissues that sits on the coffee table between them.

She looks down at her notes, at his ‘measure’, the metric that’s worked out based upon a questionnaire that her patients fill in no more than twenty-four hours before they see her. It indicates that he has ‘moderate to severe depression’. The measure classified it ‘mild’ last week so he’s taken a definite tumble. Amy knows the street that he lives on. She knows almost all the houses on that street are about four times the size of her flat. Amy’s twenty-six and has a three-year-old who, with the help of her mum and ex-boyfriend, she juggled looking after with finishing her university course and qualifications to work as a mental health counsellor. She likes Charlie. His problems are by no means the most severe of her patients, his financial and family situation one of the most stable, but she still finds him one of her most challenging clients, in many ways one of the more upsetting. There are very few people she sees that are depressed at not being able to talk to anyone about the future of infrastructure in urban centres.

ELEVEN

8 weeks

‘And what was the date of your last period?’ Naomi’s midwife, Lillian Babangida, asks, face inches away from the form she’s filling in.

Crinkled coloured paper flutters on the wall as a result of the fan heater blasting behind her. The children’s centre is one step up from a portacabin, standing in the shadow of a 1970s primary school, and they’ve covered every wall with children’s artwork in an attempt to warm up the utilitarian interior. Splodges, handprints, smears, footprints, potato shapes of various colours, collages of metallic paper, feathers and an orgy of glitter. Charlie has to keep getting up to stop Prue pulling things off the wall before sitting back down with her on his lap, trying to be attentive to the midwife until the toddler slides down to the floor and the whole music-hall routine begins again. It’s getting on Naomi’s nerves. He’d insisted they all come along to support her even though she said it was unnecessary.

She fishes in her bag for her phone so she can check ‘Ovul8’. She’s sure her last period began on the thirtieth of August. She’s seen that date marked in dark red on the app, must be nearly a hundred times since she realised she was late. But her brain’s felt so addled recently she’s lost all confidence in her surety of anything so she has to check.

‘First of September,’ Charlie declares, clutching his iPad-sized smartphone. Naomi looks at him as if he’s clinically insane. ‘That’s what I’ve got.’ He waves the phone in the air in front of him.

‘The first of September,’ Lillian says.

‘Is that right?’ Naomi says, stopping Lillian’s pen. Charlie hands Naomi the phone and 1 September is circled in dark red; he’s right. Then a green circle arrests her attention, bright green, a green that, with the brightness settings on the vast smartphone set far too high, feels vicious. The green surrounds the number fifteen: 15 September. ‘This can’t be right?’ she says. Lillian gives Charlie a look as Naomi pulls her phone out of her bag and goes into the app. There it is: 30 August circled in dark red. Big, green ovulation day: 13 September. D-Day. The D-day that started so inauspiciously but did result in a not unpleasurable lunchtime shag with her husband. She hands the phone to Charlie. His face creases with confusion as he looks at the incongruity.

Lillian’s amused by these two polite young people getting crinkled by something on their phones.

‘Clap, clap, clap.’ Prue has marched over to Charlie and is demanding one of their phones. ‘My phone. Clap, clap, clap.’ This refers to an animated video of the song ‘Wind the Bobbin Up’ that their daughter could watch on a loop until the end of days. Naomi stares into her handbag as if the polka-dot lining might have an answer to the question. Whose phone is right? He puts in when her period starts and stops so it must be his phone. But it’s always synced before.

‘It’s meant to sync up,’ Charlie says as if reading her mind. ‘Anyway, the— It’s only to work out the due date, right?’ he asks Lillian who nods, smothering a smile that they could read as being cruel. ‘Let’s split the difference and say the thiry-first, yeah?’ he defers to Naomi and she can tell that, with Prue now trying to wrench his phone out of his hand, he wants to get the form filled out and get home as soon as they can.

‘OK.’

‘When you have your twelve-week scan, they can give you a more accurate due date,’ Lillian says.

They proceed to fill out the rest of the form together. Naomi gives one-word answers. Charlie has given in to Prue and she sits on his lap watching her video six times in a row. At the end of the appointment, Lillian asks if either Naomi or Charlie has any questions. Charlie looks at his wife, expectant. Naomi always has more questions. There’s a list of them writt

en in biro on a journalist’s notepad in her bag but they’re not important now. Charlie misinterprets her vacancy for tiredness and takes over with charming ‘thank yous’, taking Lillian’s phone number and the gathering together of Prue and her detritus.

Naomi has a question, a fundamental question, but it’s not one that anyone in the room will have an answer to. Because no one else in the room, not her midwife, her husband, not even her daughter, knows what she did in a shower cubicle of a public swimming bath on the fifteenth of September.

TWELVE

10 April 2001

MSN Messenger

(*)ELIZA(*) says:

Karin? Says you’re online ….

Where you been for THREE weeks?

Miss Sindall kept me behind to find out what was going on

No one really thinks you did it

Until you stopped coming to school!!!!!

I called your house and your parents said you weren’t there

Where are you??????????????????????????????????????????

THIRTEEN

The sun here purifies the sky somehow. When clouds hang above the sea the whole coast seems suffocated but when they clear, the palette changes and it feels like a different country. The horizon, broken only by the optimistic pylons of offshore wind farms and ancient tanker ships that feel like they shouldn’t exist in the age of drone strikes and Amazon Prime, lengthens out over the sea and it could be anywhere on the other side. The fact it’s Essex is something that, when the weather’s like this, everyone pretends they don’t know. The wind is up and the sea bursts into pockets of whiteness that remind Naomi of clashing beer glasses from a Disney film she watched when she was a child.

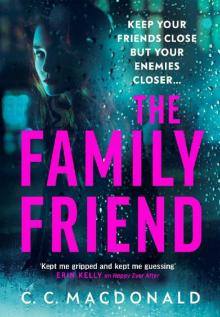

Happy Ever After

Happy Ever After The Family Friend

The Family Friend