- Home

- C. C. MacDonald

Happy Ever After Page 9

Happy Ever After Read online

Page 9

‘You went to the cinema in the afternoon—’

‘Have you been spying on me?’

‘You left the receipt in your pocket.’

‘You went through my pockets?’

‘You’re not even good at lying.’ She sees in his face she’s scored a hit.

‘I went to see Blade Runner because I wanted to see it and—’

‘You were meant to be working. During the day, you are meant to be working,’ she hisses. He looks at her, his eyes telling her how petty he thinks she is but she stares him out, the implication of every grievance she has with him, for his delusions of greatness, his inability to knuckle down and provide for them and for what happened with the house, her dream house, that, if it weren’t for him, she would be living in now, swirls like a blizzard in the space between their faces. He turns back into his seat and slumps down, putting his head back, eyes closed, and he sighs so long it could have been his final exhalation. The cinema gets darker as the trailers begin. Naomi twitches, adrenalin pumping into her brain, but Charlie’s not engaging. This isn’t what he does. This isn’t how it goes. He moves in halted movements like an insect in a jar and he swallows his words and he punches his knuckles but this, it’s like someone has pressed the off switch. She sits still and waits for him to resurface.

‘You’re right,’ he mumbles.

‘What?’

‘You’re right to be angry.’ His eyes are still closed and he speaks too loudly. A punter two rows in front turns and gives them a look. Naomi eyes Charlie, wary of what this uncharacteristic strategy might be. He says something but she can’t hear him, she bends her head down to him.

‘What?’

‘I’ve let you down. I’m letting you down.’ She can’t see, but she thinks from his breathing that he might be crying. He turns to her, blinking the beginnings of tears away and then looking squarely at her.

‘You, you and Prue, mean everything. You do. I’m going to be better. For you, I’m going to get better.’ He’s speaking in full voice now and people in the rows in front look back at them with open contempt now the trailers have begun. ‘Do you believe me?’ he says, eyes pleading. She feels the embarrassment of the whole cinema looking at her, the sensation a woman must have if she’s subject to a proposal on live TV, so she nods and gives him an understanding smile. He grabs her head into his shoulder and kisses her hair. She feels his warm breath and is reminded of Sean, of the shower cubicle. She nuzzles further into her husband to rid herself of the thought. She should tell Charlie about the baby. Now would be the perfect time to tell him that she’s pregnant with their child. She could whisper it into his neck.

‘I do love you,’ she says instead. She means it. He’s not perfect but he’s made sacrifices for her too. He’s turned down opportunities to go and work at MIT in Boston to stay with her; he agreed to have Prue much earlier than he thought he’d have children to fit in with what she wanted; he moved their life out of London, away from his friends, away from the buzz of innovation at the Hackney Wick ‘incubator’ for start-ups he used to work at, when she decided that it was the right time. He’s a good man who is struggling and she is his wife. It’s her responsibility to help him through this. She moves her head from his neck on to his shoulder and watches the trailer for some period film, an adaptation of a book she read years ago about a young couple who’ve just wed and are filled with anxiety about consummating their marriage. Charlie puts the bag of popcorn on the armrest between them.

SIX

‘You’ve got no shoes on, Prue,’ Imogen, Prue’s key worker, who has a benign moon-face, exclaims joyfully as soon as she and Naomi enter the baby-room. Naomi looks down at her daughter’s feet and sees her pink and white striped socks. All the other nursery nurses peer over from the table full of troughing toddlers at the little girl who’s been brought in without shoes.

‘I’ll go and get some from home,’ Naomi says as breezily as she can.

‘Don’t be silly, we’ve got loads of spares.’

‘Crazy morning,’ Naomi says to the room in general as the staff turn back to their charges’ breakfasts. She scans the children for Greg as she does every morning. In the days after the swimming class she was continually alert to seeing Greg, with Sean or, worse, with his mother. She’d had brief visions of an angry blonde woman, in her head she was blonde, accosting her outside the ‘Badgers’ room in some sort of cartoon cat-fight. But it hasn’t happened and if they’d still been together, after the shower cubicle, Sean would have been contrite, he would have mentioned a wife, a girlfriend to her surely. He seemed too straightforward for that sort of duplicity. Either way there’s been no sign of Greg. Not seeing Sean has been much easier for her, she knows that, but he’d still become a part of her day and she misses the routine of him.

Prue penguin-walks over to the table and gets herself a chair to sit down. She’s always loved nursery and Imogen, it’s been one of the unqualified successes of their time by the seaside. Imogen hasn’t followed Prue to the eating area but lingers next to Naomi. She wants something but is too polite to bring it up. Naomi searches her face for the answer, which only makes Imogen smile wider and shrug hopefully.

‘Nappies!’ Naomi blurts out. ‘Shit, they’re in the car.’ Imogen bites her lip and makes an ‘Oops’ face at Naomi’s language. ‘Sorry! I didn’t mean to—’

‘It’s fine! First six months I was here I spent the whole time trying not to swear. Spent a whole afternoon once trying to make a little boy say “burger” instead of “bugger”.’ Imogen radiates warmth like a campfire. ‘Are you OK?’ she asks. Naomi is not OK. It has been two days since she found out she’s pregnant and she still doesn’t know how to tell her husband.

‘Absolutely shattered, to be honest,’ Naomi confesses.

‘Not easy juggling everything, is it?’ If only Imogen knew how many balls Naomi had in the air. ‘Prue’s always happy as Larry with a Happy Meal so you’re definitely doing something right.’

Naomi thinks she might cry so she pinches her eyes together before laughing the whole exchange away. Imogen laughs with her, putting a hand on Naomi’s upper arm. And if they hadn’t been where they were, Naomi would have embraced her and sobbed into the inviting crook of her neck for hours. Her emotions have been all over the place in the last week. She’s tried to chalk it up to what she did at the swimming pool but it’s something more than that. Something primal over which she has no control. She was affected by the hormones with Prue, but not this early. She feels constantly on the edge of tears and her mind is fuzzy; the mistakes she’s made this morning, forgetting her daughter’s shoes, nappies, they’re totally out of character. Imogen gives a deferential nod and heads towards the toddler table but then stops, a sudden look of concern on her face.

‘I’ve been telling all the parents,’ Naomi’s body tenses, ‘I’m actually moving up to the threes’ room next week, so Prue will be getting a different key worker.’

‘Oh no! That’s such a shame.’

‘I’m going to be the manager.’

‘Who’ll be looking after Prue?’ The edge in Naomi’s voice makes Imogen look at her shoes. The temperature of their exchange has gone into the blast-chiller.

‘I’m pretty sure Uggy,’ Imogen indicates a nursery nurse with a centre-parting, ‘will be looking after Prue, but it’s best to talk to reception about it.’ Naomi’s never talked to ‘Uggy’. She’s much skinnier than the other girls and far less smiley but whenever she’s seen her with the children, they seem to like her. It could have been worse. It could have been the moronic one with the tattooed eyebrows who’s always on her phone when Naomi looks into the nursery garden on her walk through the park to work.

As she walks into reception towards the beanpole figure of Lisa holding the door open, she realises that everyone, the nursery nurses, the little ones who looked up from their cereal, everyone in the baby-room was smiling at her, wishing her well for the day as she went. Everyone except Uggy.

> SEVEN

5 weeks

Naomi sits at her desk in the corner of the warehouse, which, on a bright winter day, is bearably cold. It used to belong to a removals company but now resembles something from an episode of Scooby Doo. Almost all the old buildings in the area were allowed to fall into disrepair when low-cost flights to Spain robbed the town of its tourist trade and its purpose. Victoria was attracted to the building’s history and, as sunbeams catch ancient motes of dust, Naomi can see the appeal for someone with her sensibilities. But as the smell of Matilda’s Thai Curry Soup wafts over from the microwave, Naomi would happily trade it in for a nice, soulless, segregated office space.

Naomi’s working on a press release that she can’t get right. Words have dropped out of her head today. She’s used ‘wonderful’ and ‘amazing’ three times apiece. The smell of lemongrass turns her stomach. She gets to the end of a passage about the festival’s ‘amazing’ street-food offering that will insist on sustainable cardboard packaging, when the buzzer for the intercom jerks into the cavernous space. Naomi ignores it, assuming Matilda will rush out of her nook at the first excuse to stop working, but she doesn’t appear. The buzzer keeps snapping, a robotic dying bird. It’s insistent, rude almost. It’s not the tentative buzzing of the delivery man who will take the parcel back to the depot, nor one of Victoria’s fabulous friends just dropping by with a box of Florentine biscuits. Naomi saves the press release, closes the laptop and heads towards the door. Worry burns up her back and, as she reaches for the intercom’s receiver, she gets that deep sense of dread and pictures a gang of hoodied youths standing menacingly outside the door. There are boys that sit smoking on the steps of the multi-occupancy block she walks past to get to work who look at her with the most frightening hunger. She puts the receiver to her ear.

‘It’s Naomi’s husband Charlie.’ Her skin stings with goose bumps as abstract fear becomes concrete. What’s he doing here? She wants to replace the receiver, go over to a corner of the room and maybe he’ll go. ‘Can I … come up?’ His tone’s inscrutable but she can tell he’s not planning on leaving.

He knows. That’s the only logical explanation. He’s never come to her work before. She’d offered to show him round and he had no interest. He must know.

She presses the button on the intercom quickly, as if pulling off a plaster, hears the buzz of the lock and Charlie clicking into the door downstairs. Naomi turns and heads away from the door like a duellist walking their ten paces. Just as she turned away from Sean in the shower, pretending she didn’t know he was there, she wants to delay facing the consequences of what she’s done to Charlie for as long as she can. She stares out of the window, glass reinforced by chicken wire, hears him open the door and then it sounds like he’s running and she turns just at the moment that her husband grabs her round the waist and lifts her up in the air and he’s happy. He’s beaming. When he puts her down she sees he’s holding a pregnancy test. Not knowing how else to respond, she hugs into him again. Then he’s whispering short sentences that seem to overlap each other.

‘We did it. I love you. I’m sorry. We did it. Are you OK? How you feeling?’ And she mumbles and nods and now she’s crying. Really crying. A flood of tears that’s been dammed up ever since she saw the word pregnant on the plastic stick breaks her defences. He holds her tighter and his body tells her that he believes this is a watershed moment, but she knows that there’s never any such thing and even if there were, there can’t be for them, not any more. She sees Victoria glancing down at them through the glass door of her upstairs office with venomous curiosity.

‘Shall we go and get a coffee?’ Naomi says, pulling away from Charlie. He nods and taps the pregnancy test on the back of his hand before realising it could still be covered in pee.

‘Do you want to keep this?’

‘Yes please,’ she says and grabs it from him too fast. She hasn’t moved the pregnancy test since she put it away in a sealed pocket at the bottom of her handbag. So how does Charlie have it?

They’re in the same café that she went to with Sean. Charlie suggested it. The same hipster man-children are there at the same table. One of them wears a headband over his long hair now so he looks like an eighties rocker. She steals a side-glance at them, conscious they might recognise her from before. Luckily, with their over-loud Home Counties accents competing to talk about the various house improvements they’re doing, they seem entirely disinterested in anyone else in the café.

Kids run riot between the replica Eames chairs as Charlie bustles between them carrying a tray. Some people talk a good game when it comes to doing everything for their children but the parents here have come for the artisan coffee and to talk to people like them in a décor that resembles something they’ve seen on Instagram and sod it if their child has to fight with ten others to play with the lone Ikea kitchen. She resolves to take Prue to the soft play in the future rather than here. The soft-play is also more anonymous. Charlie puts the tray on a next-door table and from it produces a huge doughnut. She raises a dubious eyebrow.

‘Zygotes like doughnuts, don’t they?’ He unloads the coffee and takes the seat opposite her, pleased with his joke. She wants to ask him why the fuck he’s been going through her handbag but she knows she now has several vertical miles to climb to reach the moral high ground. She decides to get ahead of him, to cut any questions he might have off at the pass.

‘I did the test without you, I know, but I thought, after the year we’ve had, if it hadn’t been anything …’

‘It was nice, actually.’

‘What was?’ She smiles wider.

‘You leaving the test out for me to find.’ She didn’t leave the test out for him to find. She left the test hidden in the bottom of her bag. She picks up the doughnut and bites into it.

‘You found it?’ she garbles through dough.

‘You left it in the middle of the worktop; I know I’m not the most observant but even I couldn’t miss it.’ He sips his macchiato and leans back in his chair. He seems so relaxed now, like he’s just finished moving house. Naomi’s sure she didn’t leave the pregnancy test out. Her mind’s been a fug and she’s been making mistakes, mistakes she would never normally make, but she can’t have forgotten that she left her pregnancy test out on the worktop. She reaches into the handbag sitting next to her on the bench and feels around the inner lining. She knows it’s irrational. Where would he have got another positive pregnancy test? But she definitely didn’t leave it out for him to find. The pocket in her bag is empty.

‘What’ve you lost?’

‘Was there anything else with it?’ she asks him. She took some things out of her bag in the kitchen yesterday evening and perhaps it fell out somehow.

‘What do you mean?’

‘Was there other stuff with the test?’

‘It was on its own. Did you not want me to see it?’ Charlie shifts forward in his seat. Naomi knows she can lie now, she can dismiss it and focus on their joyful news. That’s what he wants to do, she can see the desperation in his eyes, pleading with her not to do or say anything that might tarnish the relief she can see radiating off him, but now she’s really worried. She couldn’t have left it there by accident. It’s Charlie who loses Prue’s sippy-cups and has his phone fall out of his pocket and leaves their front door open. She doesn’t make mistakes like that.

‘I did the test the morning before we went to the cinema.’

‘Makes sense you were in such a funny mood now.’

‘Imagine if I’d miscarried or something. It happens a lot and I wasn’t sure, with, you know, you at the moment.’

‘Me at the moment?’

‘Your depression.’

‘Right.’

‘I wasn’t sure how you’d handle something like that.’ He looks down into the splash of foamed milk on the saucer of his espresso cup and breathes out. Then he reaches across the table, takes her hand in his and rolls her fingers in his palm, his fingertips pressing int

o the flesh at the top of her hand. It’s a gesture straight out of a television drama.

‘I meant it. What I said at the cinema. I’m going to be better now. I will be. You don’t have to worry about me any more. It’s just great. Isn’t it? It’s going to be great. Nothing’s going to go wrong now,’ she goes to interject but he knows she’s trying to moderate his conviction, ‘it can’t. We deserve that. You, you deserve that.’ His sincerity drills into her and the moment to tell him that she didn’t leave the pregnancy test on their worktop for him to find as a delightful surprise when he made himself a cup of tea has passed.

EIGHT

https://www.pregnancyforum.co.uk/b841/forgetfulness-in-pregnancy – jjlapp43

Why am I more forgetful now that I’m pregnant?

A large proportion of women say they become forgetful during pregnancy, or get what’s known as ‘baby brain’ or ‘pregnancy brain’.

Nobody’s completely sure why it happens. It could be to do with your perceptions when you’re pregnant. Your memory is pretty much the same as before but you’re more tired, making focusing hard, and you probably have more on your mind now you’re pregnant. This is particularly the case for second or third pregnancies where there’s less opportunity for mum to rest.

‘Baby brain’, which also affects decision-making, has been shown to start in the first trimester and stabilise in the second and third trimesters. Its effects are therefore most prominent in the first twelve weeks and symptoms can present themselves before some mothers even know they’re pregnant.

Happy Ever After

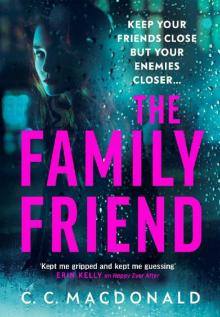

Happy Ever After The Family Friend

The Family Friend